Deploying AI Models in the Cloud Comparisson

Exploring AI, Data, and Technology

Opinion Article

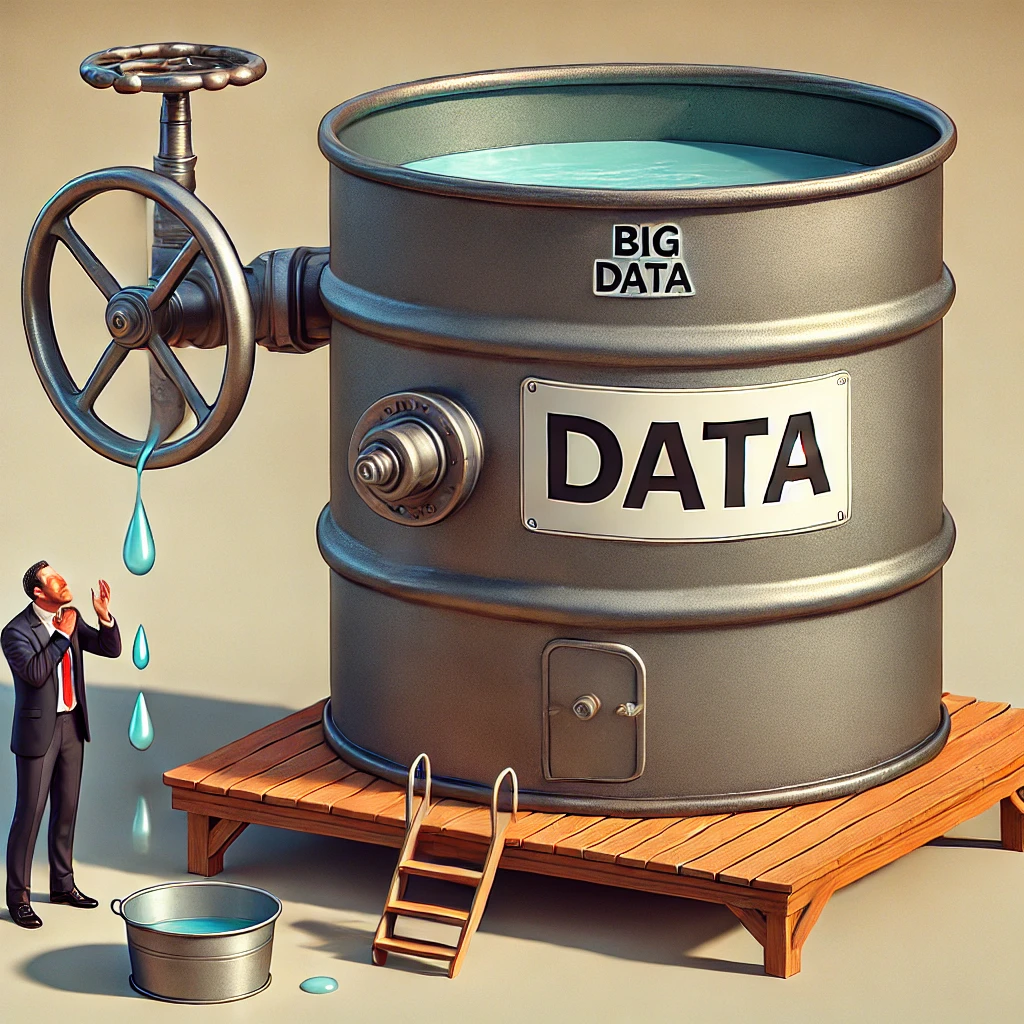

In my professional life, I've worked in several “Big Data” departments across various companies. These companies often had elaborate data architectures set up to handle large-scale data. When I graduated, the official message was that data was growing exponentially. The Internet of Things (IoT) was supposedly taking over society, flooding us with data we’d need to manage, analyze, and transform into insights. We heard that most data produced worldwide was still unexplored, just waiting to be analyzed. We were talking about terabytes—maybe even petabytes—of information. There was also talk about the need for real-time data processing, where companies required dynamic dashboards and apps to react swiftly to issues.

To deal with these supposed data deluges, companies would invest heavily in data infrastructure. At that time, most data processing was on-premise, so Hadoop was king. Tools like Apache Hive, Zeppelin, and Zookeeper, and platforms like Oracle R3, were widely used. Containers and microservices were emerging as well, and Data Lakes were everywhere. But despite all this, the reality in these companies was far different from the image sold by tech conferences and white papers. The data we worked with was often only a few gigabytes—sometimes just a handful. This “big data” was more like “little data,” far from the torrents we’d imagined.

I suspect this era marked a kind of curiosity-driven experimentation by companies. It felt trendy to have a big data infrastructure, but there was often little critical assessment of the actual data needs. So, I frequently encountered companies with robust architectures whose data volumes didn’t justify the investment. In many cases, classic relational databases and straightforward data processing scripts would have been sufficient.

There are several reasons why the data flood never happened. One is corporate politics: different departments in the same company often hesitate—or outright refuse—to share the data needed for big data projects. Another factor is regulation. Sensitive data, like medical information, must be protected, making it hard to access or use in many cases. Then there’s external data. Companies often rely on third-party providers for some data, but this data isn’t free. Every record has a cost, so companies might limit how much data they buy, and suppliers sometimes have technical difficulties or issues with data quality. When contracts and professional relationships are involved, things can get messy.

The most common reason, though, is the choice of use cases. Much of my work has focused on processing customer data for marketing analysis. The number of customers, transactions, or products can be surprisingly small for certain companies, especially when their products are high-priced. Think about how often you buy appliances or open a new bank account. In cases like infrastructure monitoring, where equipment generates signals every few seconds, the data volume is high, but for customer churn analysis, loyalty campaigns, or fraud detection, the datasets are in many cases relatively small—only a few gigabytes.

Given this context, I often found myself using big data tools and infrastructure for much smaller datasets than anticipated. I still followed big data practices, such as building processing pipelines for cleaning, formatting, and consolidating data, setting up monitoring tools and alerts, and using schedulers to run jobs at specific times. Occasionally, I would need to ingest older data into a new dataset or even rebuild datasets to correct historical errors.

A significant part of my job involved reading logs to understand why certain processes failed. Memory overflow issues were common, especially when the infrastructure was limited, causing jobs to get blocked or hang indefinitely. Deployment across different environments (development, testing, and production) was also challenging. Sometimes jobs worked in one environment but not another, and the worst cases even involved emergency changes made directly in production (not ideal, but it happens).

The funny part? Since most of the datasets were tiny, optimization wasn't usually a priority, and the big data tools often felt overpowered for the task. But the job complexities—data correction, pipeline failures, environment discrepancies—were still similar to those of truly big datasets.

Some companies genuinely need massive data processing. Just think of Google, which developed tools like MapReduce (Apache Spark predecessor) and many many more to handle the colossal data it manages. Uber processes data from thousands of rides in real time, while Netflix delivers seamless streaming to millions. This is the dream many companies aspire to, imagining themselves managing big data infrastructure like these giants.

But most companies are fine with updating dashboards once a week or month. Their core business often operates in the physical world, with clients not demanding immediate responses. Real-time data isn’t always necessary.

So, yes, some situations truly need the best and biggest cruise ships to navigate the data seas. But in many cases, a small raft is all you need for the data ponds you find yourself into. And that’s okay, the key is knowing your business and understanding the scale of the data you’re working with.